Transparent legislation should be easy to read

July 8, 2013

Legislation is difficult to read and understand. So difficult that it largely goes unread. This is something I learned when I first started building bill drafting systems over a decade ago. It was quite a let down. The people you would expect to read legislation don’t actually do that. Instead they must rely on analyses, sometimes biased, performed by others that omits many of the nuances found within the legislation itself.

Much of the problem is how legislation is written. Legislation is often written so as to concisely describe a set of changes to be made to existing law. The result is a document that is written to be executed by a law compilation team deep within the government rather than understood by law makers or the general public. This article, by Robert Potts, rather nicely sums up the problem.

Note: There is a technical error in the article by Robert Potts. The author states “These statutes are law, but since Congress has not written them directly to the Code, they are added to the Code as ‘notes,’ which are not law. So even when there is a positive law Title, because Congress has screwed it up, amendments must still be written to individual statutes.” This is not accurate. Statutory notes are law. This is explained in Part IV (E) of the DETAILED GUIDE TO THE CODE CONTENT AND FEATURES.

So how can legislation be made more readable and hence more transparent? The change must come in how amendments are written – with an intent to communicate the changes rather than just to describe them. Let’s start by looking at a few different ways that amendments can be written:

1) Cut-and-Bite Amendments

Many jurisdiction around the world use the cut-and-bite approach to amending, also known as amendments by reference. This includes Congress here in the U.S., but it is also common to most of the other jurisdictions I work with. Let’s take a look at a hypothetical cut-and-bite amendment:

SECTION 1. Section 1234 of the Labor Code is amended by repealing “$7.50” and substituting “$8.50”.

There is no context to this amendment. In order to understand this amendment, someone is going to have to go look up Section 1234 of the Labor Code and manually make apply the change to see what it is all about. While this contrived example is simple, it already involves a fair amount of work. When you extrapolate this problem to a real bill and the sometimes convoluted state of the law, the effort to understand a piece of legislation quickly becomes mind-boggling. For a real bill, few people are going to have either the time or the resources to adequately research all the amendments to truly understand how they will affect the law.

2) Amendments Set Out in Full

I’ve come to appreciate the way the California Legislature handles this problem. The cut-and-bite style of amending, as described above, is simply disallowed. Instead, all amendments must be set out in full – by re-enacting the section in full as amended. This is mandated by Article 4, section 9 of the California Constitution. What this means is that the amendment above must instead be written as:

Section 1. Section 1234 of the Labor Code is amended to read: 1234. Notwithstanding any other provision of this part, the minimum wage for all industries shall be not less than $8.50 per hour.

This is somewhat better. Now we can see that we’re affecting the minimum wage – we have the context. The wording of the section, as amended, is set out in full. It’s clear and much more transparent.

However, it’s still not perfect. While we can see how the amended law will read when enacted, we don’t actually know what changed. Actually, in California, if you paid attention to the bill redlining through its various stages, you could have tracked the changes through the various versions to arrive at the net effect of the amendment. (See note on redlining) Unfortunately, the redlining rules are a bit convoluted and not nearly as apparent as they might seem to be – they’re misleading to the uninitiated. What’s more, the resulting statute at the end of the process has no redlining so the effect of the change is totally hidden in the enacted result.

Setting out amendments in full has been adopted by many states in addition to California. It is both more transparent and greatly eases the codification process. The codification process becomes simple because the new sections, set out in full, are essentially prefabricated blocks awaiting insertion into the law at enactment time. Any problems which may result from conflicting amendments are, by necessity, resolved earlier rather than later. (although this does bring along its own challenges)

3) Amendments in Context

There is an even better approach – which is adopted to varying degrees by a few legislatures. It is to build on the approach of setting out sections in full, but adds a visible indication of what has changed using strike and insert notation. I’ll refer to this as Amendments in Context.

This problem is partially addressed, at the federal level, by the Ramseyer Rule which requires that a separate document be published which essentially does shows all amendments in context. The problem is that this second document isn’t generally available – and it’s yet another separate document.

Why not just write the legislation showing the amendments in context to begin with? I can think of no reason other than tradition why the law, as proposed and enacted, shouldn’t show all amendments in context. Let’s take a look at this approach:

Section 1. Section 1234 of the Labor Code is amended to read: 1234. Notwithstanding any other provision of this part, the minimum wage for all industries shall be not less than $7.50 $8.50 per hour.

Isn’t this much clearer? At a glance we can see that the minimum wage is being raised a dollar. It’s obvious – and much more transparent.

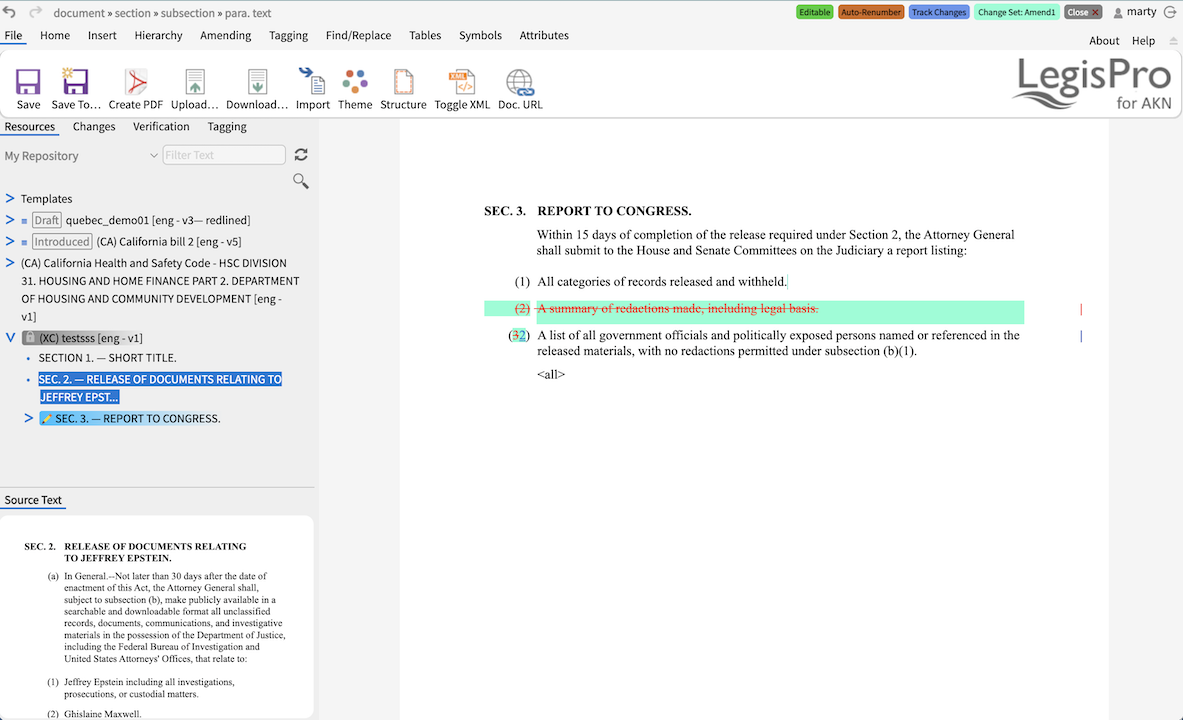

At Xcential, we address this problem in California by providing an amendments in context view for all state legislation within our LegisWeb bill tracking service. We call this feature As Amends the LawTM and it is computed on-the-fly.

Governments are spending a lot of time, energy, and money on legislative transparency. The progress we see today is in making the data more accessible to computer analysis. Amendments in context would make the legislation not only more accessible to computer analysis – but also more readable and understandable to people.

Redlining Note: If redlining is a new term to you, it is similar to, but subtly different, to track changes in a word processor.

.png)